The IMPC has identified genes associated with pain sensitivity

- 20% of adults worldwide suffer from chronic pain. 1-4

- Basic science estimates that 30-80% of the variance in pain responses can be explained by genetic factors. 5-8

- Identifying novel genes associated with pain sensitivity can lead to drug discovery to treat chronic pain.

- The search for novel mechanisms and targets for pain therapeutics is an urgent priority that led the IMPC to assess the feasibility of including a pain screen in our phenotyping pipeline.

- This work resulted in three insightful publications, details of which can be found below.

An ethical approach

IMPC Centers breeding mice and collecting phenotyping data are guided by their own ethical review panels and licensing and accrediting bodies, reflecting the national legislation under which they operate. All nociception phenotyping procedures were examined for potential refinements that were disseminated throughout the Consortium. Animal welfare was assessed routinely for all mice involved.

The IMPC has made data resulting from these experiments freely available without restriction to facilitate research and minimize duplication. In addition, the IMPC has applied the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines to ensure analyses can be reproduced.

Publications

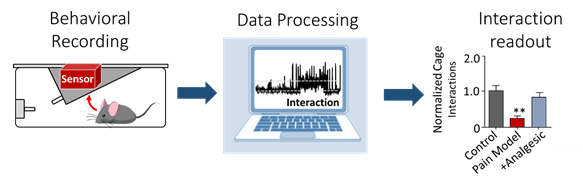

1. Cage-lid hanging behavior as a translationally relevant measure of pain in mice.

Pain 2020. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002127

Cage-lid hanging (CLH) is considered a luxury behavior displayed by mice. We hypothesized that mice experiencing pain would exhibit a reduced frequency of CLH and set out to demonstrate that time spent CLH represents an ethological measurement of pain. This publication includes a comprehensive set of challenges, analgesic treatments and pain quantification methods.

2. Machine learning-based automated phenotyping of inflammatory nocifensive behavior in mice.

Molecular Pain 2020. DOI: 10.1177/1744806920958596

The development of a reliable and scalable automated scoring system to measure nocifensive (response to pain) behavior in mice would dramatically lower the time and labor costs associated with data obtention and reduce experimental variability. We present a method utilizing video recordings and machine learning techniques consisting of three components; key point detection, per frame feature extraction using these key points, and classification of behavior using the GentleBoost algorithm. The resulting machine learning scoring system provides the required accuracy, consistency and ease of use that could make the formalin assay a feasible choice for large-scale genetic studies.

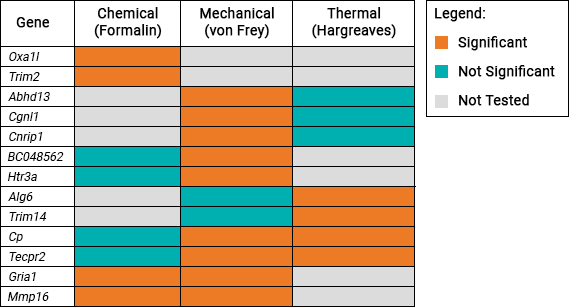

3. Identifying genetic determinants of inflammatory pain in mice using a large-scale gene-targeted screen.

Pain 2021. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002481

Knockout mice for 110 genes, many of which were hypothesized to drive pain sensitivity, were investigated. We used one or more established methodologies to study pain sensitivity in these animal models. Methodologies included sub-acute response to formalin, and von Frey and Hargreaves testing ± Complete Freund’s Adjuvant. This large scale, multi-center screening project identified novel targets and pathways involved in nocifensive behavior and provided insight into the mechanisms of response to inflammatory pain. This new knowledge can be used in studies of therapeutic target validation and drug development.

This table shows the 13 genes which were identified to be associated with pain sensitivity:

Gene list

- Mouse knockouts for 110 genes were assessed with one or more pain sensitivity assays

- These genes were assayed to determine their potential to play a role in pain susceptibility

- View additional IMPC phenotyping data by clicking on a gene name

Pain sensitivity data is visible on our gene pages, section “Phenotypes”. All data is available in our IMPC Pain 2021 paper.

| Genes Significantly Associated with Pain Sensitivity | |||||||

| Abhd13 | Alg6 | BC048562 | Cgnl1 | Cnrip1 | Cp | Gria1 | Htr3a |

| Mmp16 | Oxa1l | Tecpr2 | Trim2 | Trim14 | |||

| Genes Not Significantly Associated with Pain Sensitivity | |||||||

| AU040320 | Acod1 | Acox3 | Adamtsl3 | Agbl1 | Akr1b3 | Alad | Aqp1 |

| Atf3 | Avpr1a | Bdkrb1 | Bloc1s6 | C4b | Cacna2d4 | Cd2ap | Cdk2ap2 |

| Cenpt | Cntnap2 | Col20a1 | Col9a3 | Dnmt3b | Dusp16 | Eif2d | Emp1 |

| Esd | Exoc2 | Ficd | Foxn3 | Gabra2 | Gapvd1 | Grik1 | Grm1 |

| Hmgb4 | Ipo9 | Lamb3 | Lats1 | Lgals4 | Lrrc55 | Maged1 | Mdh1 |

| Med27 | Mkrn3 | Mme | Mrps12 | Mtg2 | Myh10 | Myom2 | Nars |

| Nav2 | Ndufa6 | Nrxn2 | Nsmce2 | Nt5dc2 | Nup155 | Ola1 | Olfr1006 |

| Otud7a | Pah | Pdcd6ip | Pex14 | Piezo2 | Pink1 | Pip4k2c | Polr1d |

| Ppp2r5c | Ptprk | Rex1bd | Rnpepl1 | Rps20 | Rsad2 | Scrn2 | Sez6l |

| Shank3 | Shisa6 | Slc17a8 | Slc24a4 | Slc30a4 | Slc7a14 | Slc9a7 | Slc9a9 |

| Stk36 | Taf13 | Tedc1 | Timp1 | Trak2 | Trappc1 | Trpc1 | Trpm3 |

| Tspan17 | Tspoap1 | Tubb6 | Unc13c | Utp4 | Ypel2 | Zfp236 | Zfp597 |

| Zfp91 | |||||||

Gene selection criteria fell into three categories:

- Nominations from domain experts

- Genes that have some pain-related association identified using the GeneWeaver tool 9

- The remainder of the genes had no known pain associations

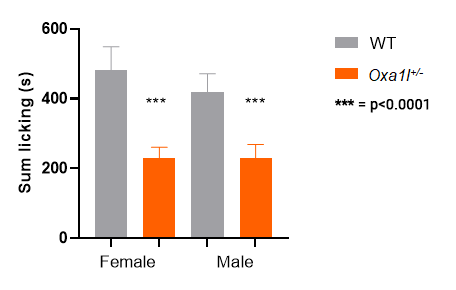

Showcase – Response to a chemical stimulus (formalin)

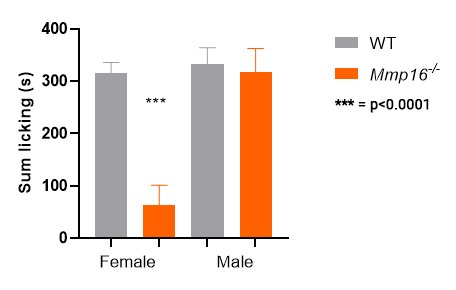

As with many phenotypes studied by the IMPC, sex is a biological variate, that is, we observe a difference in the response between males and females. 10

Oxa1l KO heterozygotes: both males and females show a response

Mmp16 KO homozygotes: only females show a

response

Approach

Details of procedures are available via IMPReSS (International Mouse Phenotyping Resource of Standardised Screens). Here is a summary of the procedures used.

| Protocol name | IMPReSS ID | Protocol purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin | IMPC_FOR_001 | Chemical nociception was assessed using the sub-acute (late phase) response to formalin. Formalin was administered via an intra-plantar injection and time spent licking or biting the injected paw in the interval between 10 and 60 minutes after formalin administration was measured. |

| Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) | CFA is not a standalone assessment, but instead is an inflammatory agent that can be administered prior to assessing mechanical and/or thermal nociception. | |

| Von Frey | HRWL_VFR_001 JAX_VFR_001 TCP_VFR_001 UCD_VFR_001 | Assess mechanical nociception in naive or CFA challenged animals |

| Hargreaves’ | JAX_HRG_001 TCP_HRG_001 UCD_HRG_001 | Assess thermal nociception in CFA challenged animals |

References

1) Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables 2016, 2017.

2) Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:78.

3) Goldberg DS, McGee SJ. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011;11:5.

4) QuickStats. Age-Adjusted Percentage of Adults Aged ≥18 Years Who Were Never in Pain, in Pain Some Days, or in Pain Most Days or Every Day in the Past 6 Months, by Employment Status — National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2016. . MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, Vol. 66:796, 2017.

5) Mogil JS. Pain genetics: past, present and future. Trends Genet. 2012 Jun;28(6):258-66. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.004. Epub 2012 Mar 28. PMID: 22464640.

6) Nielsen CS, Knudsen GP, Steingrímsdóttir ÓA. Twin studies of pain. Clin Genet. 2012 Oct;82(4):331-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01938.x. Epub 2012 Aug 13. PMID: 22823509.

7) Norbury TA, MacGregor AJ, Urwin J, Spector TD, McMahon SB. Heritability of responses to painful stimuli in women: a classical twin study. Brain. 2007 Nov;130(Pt 11):3041-9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm233. Epub 2007 Oct 11.

8) Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, Alonso J, Karam E, Angermeyer MC, Borges GL, Bromet EJ, Demytteneare K, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Lepine JP, Haro JM, Levinson D, Oakley Browne MA, Posada-Villa J, Seedat S, Watanabe M. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain. 2008 Oct;9(10):883-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005. Epub 2008 Jul 7. Erratum in: J Pain. 2009 May;10(5):553. Demytteneare, K [added]. PMID: 18602869.

9) Baker EJ, Jay JJ, Bubier JA, Langston MA, Chesler EJ. GeneWeaver: a web-based system for integrative functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 2012;40(Database issue):D1067-1076.

10) Karp, N., Mason, J., Beaudet, A. et al. Prevalence of sexual dimorphism in mammalian phenotypic traits. Nat Commun 8, 15475 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15475